Women, Art and Food

As a society, we tend to place women on the same platform as our food. Thus we make them seem equal in comparison to both inanimate and consumable objects. Both women and food are viewed in particular in visual advertising as easily obtainable to be enjoyed by our gaze and just as quickly wasted. There are many examples, such as commercials for burgers or beer in which a woman is overtly sexual even in the noises of pleasure while eating or drinking. These types of commercials suggest that the viewer should not only consume the product but the model.

Another example would be many women's magazines that directly compare different body shapes and sizes to fruit. As a woman, you may wonder if your pear-shaped or apple, unconsciously internalizing the comparison of oneself to a fruit. In this sense, art is not an exception. For hundreds of years, artists have been using the symbolism of fruits and flowers along with other inanimate objects for comparisons to the female form. Men, however, are defined more often by things they do, such as their accomplishments or their intelligence, rather than being diminished to an inanimate object. In particular, artists are likelier to compare men and strong animals, living creatures like horses and lions, to convey their power.

Another view of how women are compared to food or non-powerful animals can be found in The Sexual Politics of Meat; Carol J. Adams explains how the oppression of women and animals can be seen as co-implicated. Adams analyzes multiple representations, both visual and linguistic, in nature of women as meat(food) and of animals whom we eat as being feminized in our societal perceptions. This view makes it easier for some men and even women to treat both parties as consumable goods, along with the impression of subordination.

It is worth mentioning that there are parts of the female body which are edible and can be viewed as food. The edible products produced by most female bodies include breast milk and the placenta, often regarded as ‘gross’ food by anyone other than their infants who depend on this production. In 2006, performance artist Jess Dobkin’s “Lactation Station” pasteurized breast milk bar prompted Health Canada to warn about consuming breast milk. While drinking breast milk may not be the best option for adults, it is alarming the mixed information women receive through the media and social expectations. Women are often bombarded with the expectation to produce and provide natural milk to their children and are sometimes undermined for seeking alternatives.

Meanwhile, their milk can be perceived as disgusting, and breastfeeding in public is frowned upon in many societies. Despite its source of proteins, eating the placenta is still commonly regarded as disgusting in many ‘Western’ societies. There are exceptions, of course, in particular with the wealthy classes who can afford to transform these female made foods into a more ‘proper’ form of consumption, such as pill form. Presently, women are edible only as flesh and primarily as a metaphor for sexual consumption, which can be seen in our everyday lives, including hundreds of years of art creation. I am doubtful that this association of women with consumption and food is an inherent property but rather a social construction.

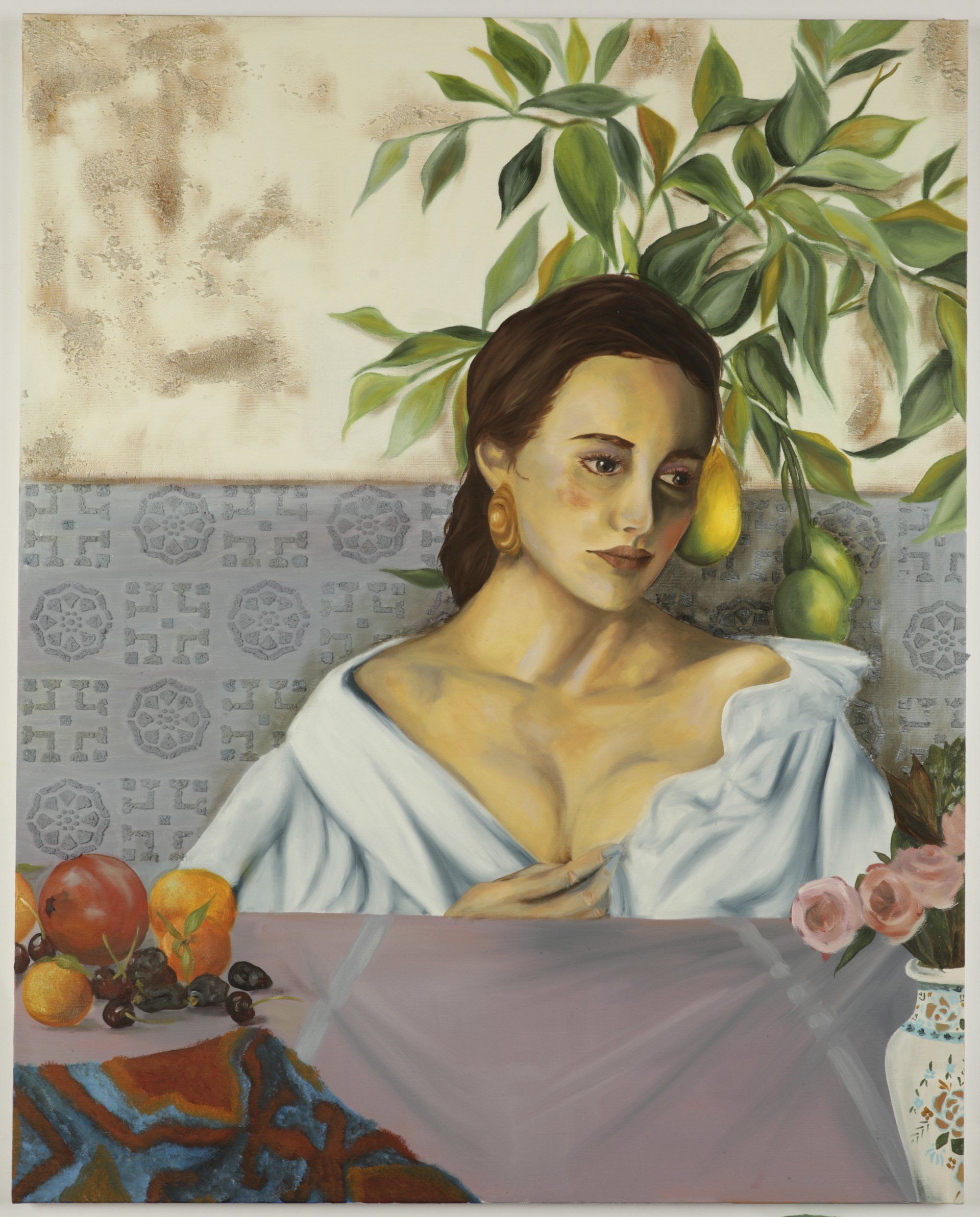

In my painting entitled Fruit For Thought, the fruit depicted needed to be about her blooming thoughts. It is meant to portray the feeling that life and ideas were being sprouted around her head. The bright fruit (a ripening lemon) signifies the ever-powerful life inside and behind her eyes rather than a comparison to her figure. This being said, I chose not to hide her figure as I think a woman can have both their natural-born figure to be proud of along with their blooming thoughts. One attribute does not discount another, and so I felt that showing more of her chest was not in a sexual sense, but instead, it can represent her actual body without a sense of shame. I sought to capture the innate essence that there is more happening inside her head than what we, the viewers, get to see and know. Just because part of her form, her chest, is exposed to the viewer does not mean she as a person is exposed to us. She can be seen as more than her figure and, in this sense, is a mystery to the viewer as we see only her exterior and must ponder on what the interior and inner self may be.

Women, Art and Food, have a historical and multifaceted relationship that, as an artist, I draw from a lot; I cannot help but feel a connection to these themes. When painting food, there is a long-standing connection with women. The trend for kitchen, market scenes, and still lives often shows the viewer an abundance of food and imagery of young women, originating with (male) Flemish and Dutch artists working in the early 16th century known as the Dutch Golden Age. These genres of painting were borne from the desire to move away from traditional religious imagery, due partly to the rise of Protestantism in the Dutch Republic during this period, which warned against the use of pictures in worship and spawned events like iconoclasm. These new, food and object-oriented categories attracted women artists because, unlike history and religious painting, they did not require access to live models, which in this period (until the late 1800s) was restricted to male artists. It was not seen as appropriate for women to be able to practice art in Western culture as professionals. When it was somewhat allowed, it was inappropriate for women to study the body or nude (of either women or men). The still-life paintings tended to be smaller and could easily be painted at home rather than in an artist's studio allowing access to the domestic women of the time. Such issues mattered at a time when, except for some aristocratic ladies and painters’ daughters, becoming a professional painter remained out of bounds for many women.

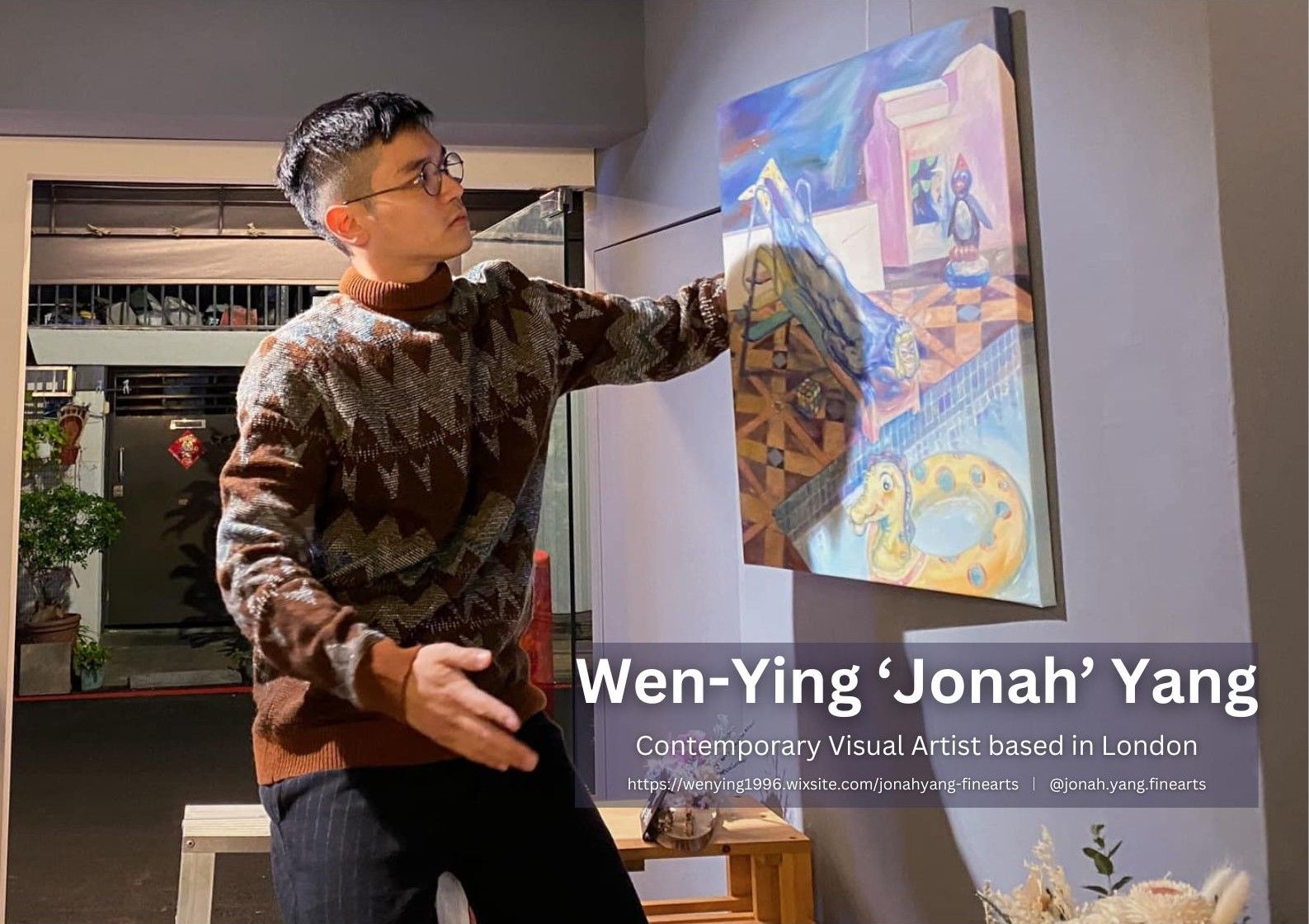

As a Canadian female artist, I like my work to have a dialogue with art history, including that of women and art in particular. While I enjoy the practice of still life and its connection to female painters, I enjoy expressing thoughts and themes through the figure. I tend to blend figure works with a still life to create an exciting composition. The blending of genres allows me to have my modern views and interpretations on how to express female figures and forms while exploring the tradition of still life and its direct link the everyday life.

Sources :

Croizat-Glazer, Yassana, A Women’s Thing, and Morgan Everhart. “Moving Feasts and Still Lifes: Food, Art, and Women in History.” A WOMEN'S THING, July 29, 2020. https:// awomensthing.org/blog/food-art-women-in-history/.vDouglas , Emily. “Eat or Be Eaten: A Feminist Phenomenology of Women as Food.” Accessed July 27, 2022. https://phaenex.uwindsor.ca/index.php/phaenex/article/download/ 4094/3171. Grieco, Allen J. Food, Social Politics and the Order of Nature in Renaissance Italy. Florence, Italy: Villa I Tatti - The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, 2019.